Housing distress in West Belfast: the view from MUMO

Poor housing conditions intensify complex local issues. MUMO supports any move to increase the public housing stock in west Belfast and across the city and region. There is a chronic need for durable, quality public housing which can contribute to good quality of life for local residents, meeting their basic needs.

Moving Up Moving On (MUMO) is a project based at Forthspring Inter Community Group. MUMO provides holistic family support to families from two local primary schools – St. Clare’s Primary School and Springfield Primary School. Both are situated in areas experiencing multiple disadvantage as identified by the Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency (NISRA). MUMO employs two children’s support workers (based in the two schools), two family engagement workers, based in Forthspring and a manager.

Some of the families which MUMO works with face many complex issues but the two most serious, most prevalent and most difficult to overcome are poverty and housing distress. Both are interrelated.

In this blog, I am going to briefly describe the housing conditions of two families we work with.

Case study one

Niamh (not her real name) is a lone parent with a school age child and a new baby. She lives on the third floor in a new flat on the Springfield Road. The apartment is owned by a housing association. She has lived there for two years and the flat was new when she moved in. Niamh says it is a nice apartment and the block is quiet which she appreciates, having two very young children.

Despite this there have been issues:

• There is no garden which means the family do not have access to outdoor space, increasingly recognised as crucial for physical and emotional wellbeing

• The lift keeps breaking. Since her youngest child was born 12 weeks ago (at the time of the interview), the lift has broken three times – on one of those occasions, it was broken for five weeks. When the lift breaks, Niamh is very housebound as it is so hard getting a buggy up three flights of stairs. Niamh always reports when the lift is broken and keeps a record via email.

• The roof has had several leaks and has had to be fixed on more than one occasion. Slates on the roof seem to keep falling off. On one occasion, Niamh’s ceiling completely collapsed, which could have caused serious injury

• There are cracks in the plasterwork throughout the apartment – the building does not seem to have been finished well.

Niamh is very proactive about reporting faults. Despite this, it can take weeks for problems to be resolved (e.g. the lift being broken for five weeks).

Case study two

Aoife (not her real name) is a lone parent with two school age children, both of whom have been diagnosed with autistic spectrum disorder (ASD). She is currently pregnant. Aoife lives in an apartment off the Springfield Road in west Belfast and has been there for three years, since her youngest child was a baby. The house is completely unsuited to the needs of Aoife and her children. There is no garden. To access the flat, Aoife and the children have to climb 30 steps, from the street to her front door. Fifteen of these steps are concrete and the other 15 are carpeted. There have been many days when Aoife was unable to leave the house as it was so hard getting a buggy/two young children up and down the 30 steps. Aoife has to leave one child at the top of the stairs, bring the other child down, leave that child at the bottom of the stairs and go back for the other child every time she leaves the apartment. The youngest child has fallen badly three times on the stairs and has been taken to hospital.

It is a two-bedroom apartment which is extremely challenging as both children need their own room because of their ASD. Having to share bedrooms impacts on the children’s sleeping which in turn impacts negatively on school attendance.

Aoife has also experienced consistent noise issues over a six-month period. This impacted on the family’s sleeping. It was so bad that Aoife was awarded extra points.

In terms of access to resources, Aoife lives 20 minutes’ walk from the nearest shop and 25 minutes’ walk from the nearest park. This is extremely unsatisfactory and means the children do not have easy access to any outdoor space. This apartment is suitable for a single person or a couple with no children, not a family. Fortunately, after three years’ of living with these difficult conditions, Aoife was offered suitable accommodation.

* * *

These are two examples of many which MUMO has encountered since it began in 2016. A significant amount of MUMO’s family engagement work involves support around housing needs. Adequate housing is a basic human right. Access to outdoor space is crucial for children’s development. It contributes to improved physical well-being and improved emotional and intellectual health. Nature experiences can have a restorative effect for children making time spent in nature, whether that is a garden or a local park (for urban children) particularly beneficial. Lack of access to outdoor space is an issue for many of the families we work with.

The Guardian reported in 2014: ‘avoidable disease and injuries caused by poor housing costs the NHS at least £600m a year. A safe, settled, home is the cornerstone on which individuals and families build a better quality of life, access the services they need and gain greater independence. In contrast, homelessness and poor housing multiply inequalities and have a long-term impact on physical and mental health. The health effects of poor housing disproportionately affect vulnerable people: older people living isolated lives, the young, those without a support network and adults with disabilities.’

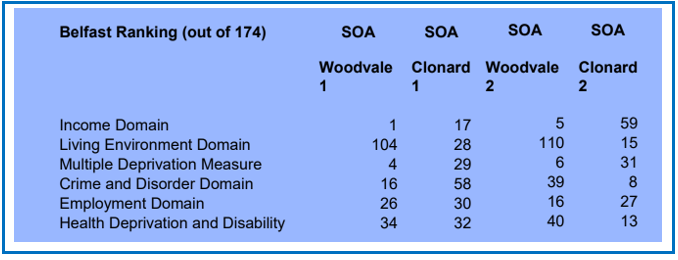

NISRA has split Northern Ireland into 890 Super Output Areas (SOAs), each with an average population of around 2100 people. Belfast has been split into 174 SOAs. Forthspring Inter Community Group is on the Springfield Road with Woodvale 1 SOA directly behind us, Woodvale 2 SOA beside us, Clonard SOA 1 directly facing us and Clonard 2 beside that. The people using MUMO services come from both the Woodvale and Clonard areas. NISRA has compiled a Multiple Deprivation Measure based on a combination of rankings of deprivation, and all four of these SOAs are among the most deprived in Northern Ireland: Woodvale 1 is the 8th most deprived overall; Woodvale 2 the 12th; Clonard 1 the 50th; and Clonard 2 the 55th. Other notable findings are listed below:

The area is affected by particularly high levels of adult suicide, at more than double the Northern Ireland average. Many households experience multi-generational unemployment. Many of the children we work with experience poverty and have medical conditions including asthma, ADHD and autism.

Social, economic and cultural benefits of the peace process have largely not been felt to the same extent as in other parts of the city and region. While the level of violence associated with the conflict has declined, what currently exists is an uneasy form of mutually-tolerated separate living.

The nearby peace line wall marks a line of residential, political and cultural segregation between the Shankill/Woodvale and the Falls/Clonard areas. Our ‘peace-line’ vehicular gate (pictured above), two doors from the building, is opened only once every year, to allow a traditional Protestant parade to pass through the gate. The pedestrian gate is opened and closed each morning and evening by a security firm to prevent incursions from one community into the other. Shankill/Woodvale and Falls/Clonard communities live with the legacy of particularly high levels of violence during ‘the troubles’, continuing paramilitary influence, and residual local tension especially during the annual summer parade period.

Poor housing conditions intensify all the above complex issues. MUMO supports any move to increase the public housing stock in west Belfast and across the city and region. There is a chronic need for durable, quality public housing which can contribute to good quality of life for local residents, meeting their basic needs. The multi deprivation indicators change little over decades, with the most disadvantaged communities remaining extremely disadvantaged from generation to generation. Policy and investment patterns need to change to reflect this to create meaningful, lasting change for people living in our most disadvantaged communities.