Housing Need in Belfast: A Closer Look at What's Changing -- and What Isn't

The Housing Executive measure of 'residual need' reflects the shortfall in social housing in any given area. A closer look at the shift in these figures since 2015 in Belfast shows deep and ongoing shortages of social housing, particularly in areas of high demand. It also reveals a growing shortfall in social homes in more unexpected areas. So what's next?

The Housing Executive’s measure of “residual housing need” is an indication of the shortfall between the serious demand for social homes in a given area and their availability. The formula for it takes into account local levels of housing stress (households on the waiting list with more than 30 points) as well as average annual allocations (the number of social homes vacated and re-let in that area).

Shortfall in Social Homes More than Doubles in North Belfast 1

The Housing Executive has identified 18 Housing Need Assessment (HNA) areas in Belfast. Its ‘residual need’ reporting indicates that the Belfast HNA with the greatest shortfall in social housing is the predominately Catholic part of North Belfast, known as HNA North Belfast 1. Here, residual need nearly doubled in recent years, from a shortfall of 690 homes in 2015/16 to a shortfall of 1,328 homes in 2022.

Shortage of Social Homes Steadily Worsens in West Belfast

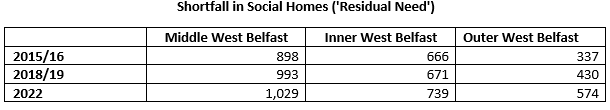

After North Belfast 1, the areas with the highest levels of residual need – in 2022 as in previous years – were the (predominately Catholic) Middle, Inner and Outer West Belfast HNAs:

In these three Housing Need Assessment areas, the 2015/16 shortfall in social homes against objective housing need has not only remained unmet, it has grown. This is one reason why plans for the 20+ acre Department for Communities-owned Mackies site in West Belfast – by far the largest piece of available public land in the city – must include social housing, to complement the cycle paths and vacant green space currently foreseen for the site under Belfast City Council’s Forth Meadow Community Greenway scheme.

Emerging Shortage of Social Homes in Previously Unaffected Areas

Some parts of Belfast historically showed a only a very slight gap, if any, between serious need for homes amongst households in housing stress and social housing availability – their low ‘residual housing need’ indicated that any local demand for social housing was fairly well covered. In numerous HNAs this appears to be changing.

In north Belfast, for instance, the predominately Protestant North Belfast 2 showed a shortfall of 24 social homes in 2015/16, which by 2022 had grown to a shortfall of 133 homes.

Similarly, Inner East Belfast HNA’s residual housing need amounted to 102 social homes in 2015/16, but by 2022 had more than tripled to 348 homes; while Outer East Belfast, with a residual need of 123 in 2015/16, showed a shortfall of 297 in 2022.

What Are the Authorities Doing About This?

The Department for Communities’ Housing Supply Strategy – for 100,000 new homes across the north over the next 15 years – will hopefully help address this need; but the devil will be in the detail. While the Communities Minister has stated that she wants at least a third of the new homes to be social housing, there is currently no mechanism in existence that would make that happen.

If anything, the weight of existing policy would appear to be in the opposite direction.

Belfast City Council’s draft Local Development Plan strategy includes an aim of 31,600 new homes – for a planned 66,000 new residents. It does not address the growing shortages of social housing amongst existing residents, documented year on year in the Housing Executive’s ‘residual need’ reporting, across the city. Its policy HOU5 would mandate that all new residential development include 20% ‘affordable’ units; but Council’s draft supplementary planning guidance on affordable housing, setting out how that would be administered, shows little focus on objective need and extremely limited scope for a meaningful role in decision-making for the Housing Executive – the one body tasked with tracking and responding to growing housing stress and homelessness.

Moreover, for its part the Department for Communities has in recent years re-defined ‘affordable housing’ in policy. Up to 2020, ‘affordable’ meant either social housing or co-ownership. Under a growing raft of new policy instruments, however, the Department has steadily expanded this to incorporate a host of additional ‘intermediate housing options’ aimed at people on median incomes.

The result? Belfast City Council’s stipulation that 20% of new housing be ‘affordable’ could be followed to the letter without a single new social home being built anywhere in the city.

The likely outcome, given these various factors, is that the social housing shortfalls across the city described above will become ever deeper and more entrenched – leaving families living in the most acute housing need farther and farther behind.