Policy Watch

An eye on policy changes in Ireland, the UK and beyond

Housing need overview | Temporary accommodation framework | Reliance on temporary accommodation | Impact of temporary accommodation on children in hotel settings

Figures from the Department for Communities (DFC) show that in the first six months of 2023, over 8,500 households presented to the Housing Executive as homeless. Such a figure is not new in itself; DFC records (table 1.1) show that some previous years have seen slightly higher, some slightly lower). According to DFC data (table 1.3) the areas with the highest number of people presenting as homeless (and the highest incidence of homelessness per 1,000 people) remained, as in previous years, Belfast and Derry – with significant need elsewhere as well.

In the first half of 2023, just over three fifths (62%) of those presenting in search of help to house themselves were judged to have met the Housing Executive’s tests of homelessness, eligibility, priority need and intentionality, and accepted as statutorily homeless. This official Full Duty Applicant status translates to an additional 70 points under the Housing Selection Scheme used to allocate social homes, and a formal responsibility on the Housing Executive to provide the person or household with accommodation.

DFC figures from September 2023 indicated that there were 45,615 households on the social housing waiting list (up from 45,105 in March); at the same time the number of households recognised as Full Duty Applicant homeless across the north had risen to 27,566 – an increase of nearly 5% in six months (the March 2023 figure was 26,310).

What options do people officially recognised as homeless have?

The DFC reported that in the year ending 30 September 2023, 5,586 social homes had been allocated, roughly 70% of them to new tenants (the remaining 30% of allocations were transfers between social homes, by people already holding a social tenancy.)

The Housing Executive reported to the All Party Group on Homelessness in January 2024 that roughly nine out of ten allocations are to households with FDA status. Even so, given the slow turnover in social housing tenancies and the low rate of new building and acquisitions as compared to demand (the 2022/23 targets were 1,950 social home starts and 1,400 completions), at the end of each year the majority of homeless households remain in limbo, still waiting to be allocated a home. What happens to them?

Temporary accommodation framework

Households who are recognised as ‘legally homeless’ under the Housing Executive criteria, or who are being assessed and who are believed to meet the criteria, are placed into temporary accommodation by the Housing Executive. With the Covid pandemic the Housing Executive upped its temporary capacity by 650 units (Ending Homelessness Together strategy 2022-2027 (p. 11)); but the system remains overstretched.

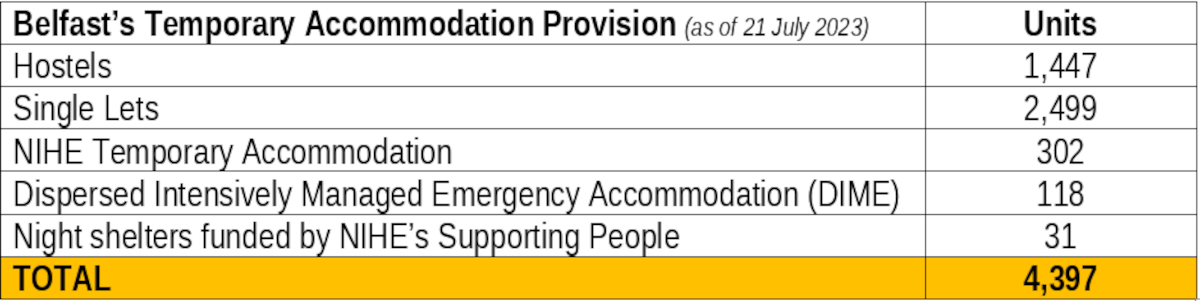

According to the Housing Executive’s Draft Strategic Action Plan for Temporary Accommodation 2022-27 (p. 4), 38% of the temporary accommodation available to the Housing Executive is comprised of voluntary sector hostels; there is also “a small supply of Dispersed Intensively Managed Emergency (DIME) accommodation, Housing Executive properties and Night Shelter beds”.

In addition, just over half of the standard temporary accommodation available to the Housing Executive are private sector single lets. A recent Belfast City Council committee report observed that these “are often managed by large private companies, such as Homecare Independent Living. The company, rather than the landlord, will deal with the resident and the Housing Executive. Residents tend to stay longer in single lets than in other types of temporary accommodation” (p. 107).

As a snapshot, information provided in the minutes of a Belfast City Council committee, from 21 July 2023, gives an overview of standard temporary accommodation capacity (with slightly higher figures than those in the earlier Housing Executive draft action plan):

The Housing Executive’s draft action plan adds that “as a last resort, in order to meet our statutory accommodation duties, placements may be made in hotel or B&B accommodation. This is for as short a period as possible for a number of reasons; it is generally not suitable for long term stays, it is costly, and its primary purpose is within a hospitality context” (p. 4).

The Housing Executive reported to the All Party Group on Homelessness in January 2024 that spending on temporary accommodation had risen from £4.87m in 2017/18 to £19.1m in 2021/22. The percentage of the spend going on ‘non-standard’ accommodation like B&Bs and hotels – 13.7% in 2017/18 – rose to over 30% in 2021/22.

The 2022 draft action plan referred to needs assessment findings that housing support needs outstripped supply; that need was growing; and that it was increasingly complex (p. 7). However, the picture has appeared to change even beyond what was foreseen.

Unprecedented reliance on temporary accommodation

In early 2023, Homeless Connect expressed concern at the nearly doubling (a rise of 91%) in the number of households in temporary accommodation in the four years since January 2019. By the spring, data covering fiscal year 2022/23 revealed that the figure had topped 10,000 for the first time; DFC statistics (table 3.1) for the first half of 2023 indicated 5,148 placements of households in temporary accommodation (though it was not clear how many of these occurred in the first quarter of fiscal year 2023/24). In October 2023, Housing Executive chief Grainia Long told the Belfast Telegraph that record numbers of people were having to be placed in temporary accommodation.

Factors such as the rising cost of energy, fuel and household essentials have pushed some people into homelessness, exacerbated by rising rents in the private sector. From April 2024 Housing Executive tenants will see a 7.7% increase in their rent. Less obvious factors, such as the Prime Minister’s target of eliminating the backlog of pending asylum decisions by the end of 2023, have also forced more people out of their accommodation and into the offices of the Housing Executive in acute housing need.

In some cases, the shortage of both standard and non-standard temporary accommodation means that families are only offered places well outside their current area of residence.

Reports from families – some born and raised here and some newly recognised refugees – reveal that increasing numbers are being placed in temporary accommodation in hotel rooms, mainly in cities outside of Belfast - places that many of them have never been, where they know no one. (November statistics provided by the Housing Executive on temporary accommodation placements made by the Belfast team (though not necessarily within Belfast) indicated 177 placements in ‘non standard’ accommodation – which the Housing Executive clarified included accommodation in hotels – on 19 November; by 2 January this had risen to 183.)

Both new and longstanding residents have faced this situation, and the choice between being housed and being forced to leave the areas where they have put down roots over years. People in work have been moved away from their jobs, and have reported having to give up their employment in consequence. Parents have had to take their children out of school in order to take up an offer of accommodation far away. For any child, such upheaval and loss of friends and familiar surrounds is bound to be disruptive; for children who may have suffered trauma in their young lives, the impact of such change can be even more devastating. In many cases school staff have written the Housing Executive to urge that the families be located locally, so that their work with and care for the child will not be undone. Similarly, GPs and consultants have written letters urgently requesting that their patients be found accommodation nearby, so that they can attend appointments and continue with courses of care that they have already begun.

In purely practical terms, people lodged temporarily in hotel rooms do not have access to cooking facilities. Some hotels used by the Housing Executive are in remote locations, inaccessible to shops and services, and the only meals available are those offered by the hotel restaurant – at prices that are beyond the means of the people placed there. (One family reported sharing one daily hot meal between them, at a cost of £18 – all that they could afford). People are forced to live on cold prepared food that they are able to bring into the hotel; one family reported repeatedly having to feed their children bread and butter, the only thing within their means. The health risks and potential long term impacts on children’s development are clear.

Families – even those from here, who may own cars – face higher transport costs due to having to drive long distances to try to maintain work, school, family or community activities. Costs are particularly prohibitive for newly-recognised refugees who only recently received the right to work with their refugee status; while looking for work for the first time, most have applied for Universal Credit but are facing the five-week wait for the first payment with no income, no savings and no official support.

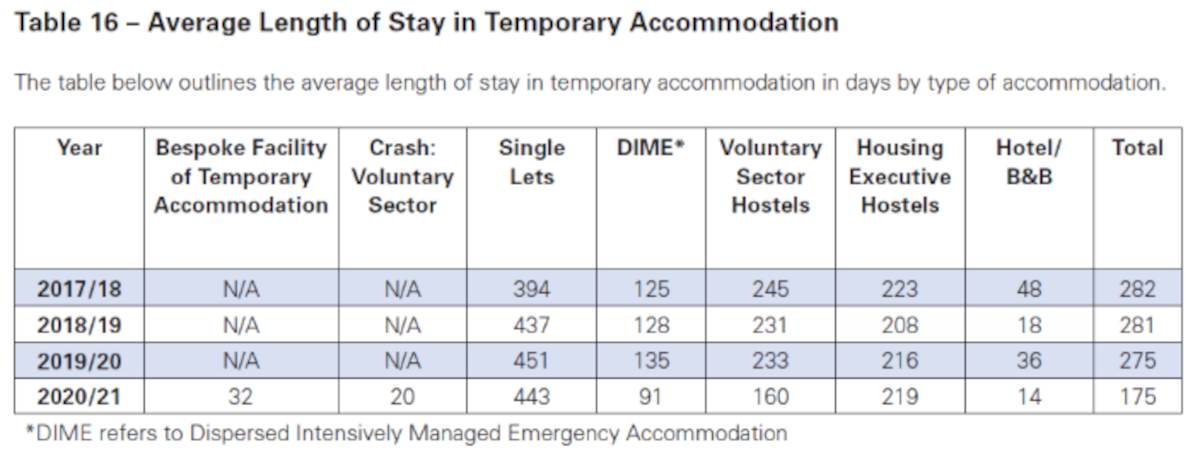

As it is not clear how long ‘temporary’ may last, people are left in limbo, unsure of whether to try to integrate into the new area or not. (The All Party Group on Homelessness was told in January 2024 that the most recent estimates (from September 2023) placed the average length of stay across all forms of temporary accommodation at over 34 weeks. The Housing Executive’s homelessness strategy 2022-27 (p. 55) set out the average length of stay, broken down by type of temporary accommodation, over recent years:

The impact of temporary accommodation on children

The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights – ratified by the UK in 1976 – recognise everyone’s right to an adequate standard of living for themselves and their family, including adequate food, clothing and housing, and to the continuous improvement of living conditions (art 11.1). UK policy acknowledges that hotels are wholly unsuitable for lengthy stays, particularly for families. the UK government’s Homelessness code of guidance for local authorities, for instance, calls such accommodation “particularly detrimental to the health and development of children” (para. 17.32) and recommends it be used for families in particular “only as a last resort and then only for a maximum of 6 weeks” (para. 17.33).

According to DFC data (table 3.3), in January 2023 there were 4,236 children in temporary accommodation, 66 of them in ‘hotel / B&B / leased property’. By end July this had risen to 4,569 children in temporary accommodation, 94 of them in the hotel/B&B category. The next DFC dataset is due in March 2024 and is expected to show further increases.

Particular rights at risk of being breached in these conditions include children’s right to develop to their fullest potential (Convention on the Rights of the Child (article 29)), their right to enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health (article 24) and their right to an education (article 28). Equally affected by prolonged stays in single hotel rooms, with insufficient space to play and no access to outdoor open space, is the right of every child to rest, leisure, play, recreational activities and free and full participation in cultural and artistic life (article 31). Official UK guidance recognises the potentially detrimental effect of hotel accommodation over prolonged periods, and has set the six-week maximum for that reason – the extent to which it is complied with will bear close watching going forward.